The Kansas/Nebraska Debate: Finding where Zebulon Pike visited the Pawnee

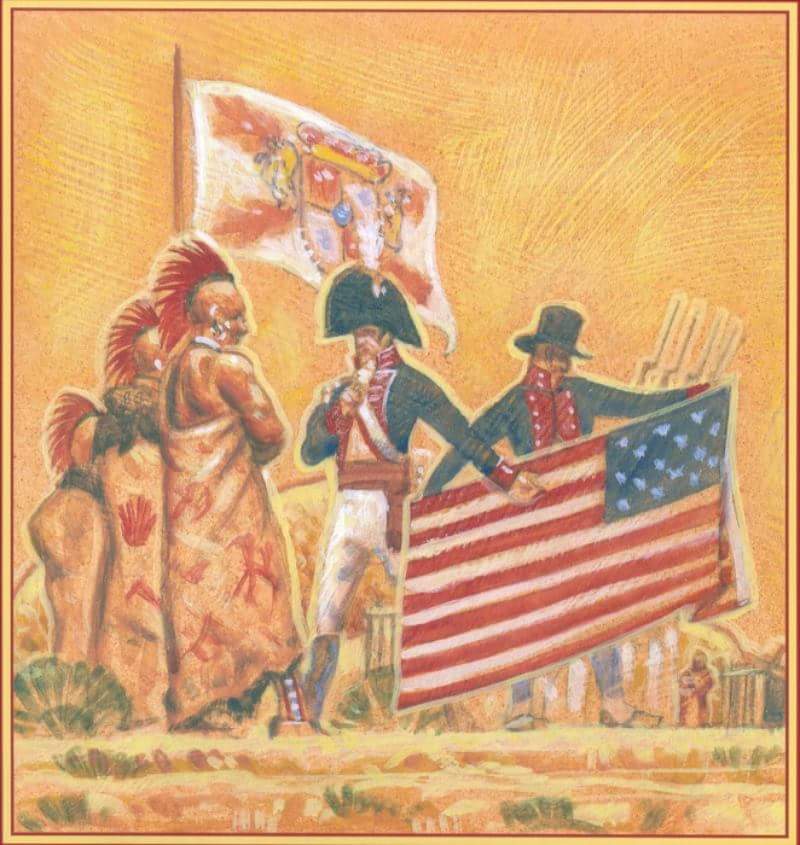

If you have ever traveled through the Kansas town of Republic, then you have no doubt seen the Pawnee Indian Museum and the white granite monument just outside the city. The monument was erected in honor of an event that didn’t even happen in the state. However, it was so widely believed that it had occurred here that it has become a Kansas legend. This event is the visit of renowned explorer Zebulon Pike to a Pawnee Indian village in 1806. Pike’s exploration of Kansas was part of his second expedition. In July 1806 he set out from St. Louis, MO on what would become known as his “Arkansaw Journey”. His route would take him west along the Missouri River to the Osage River. The party traveled overland through Kansas until they reached a Pawnee Indian village near what is today the Kansas-Nebraska border. To the white man it was known as the Republican Pawnee, the Kitkechahki band inhabited several of the Historic Villages near the border area. Just days before Pike arrived the village was visited by Spanish Lieutenant Facundo Melgares and over 300 Spanish soldiers. He left many gifts including the Spanish flag. During his visit on September 29, 1806, Pike saw these gifts and when he saw the Spanish flag flying, he demanded that it be lowered, and the flag of the United States raised. According to his journal entry from that day:

“Held our grand council with the Pawnees, at which were present not less than 400 warriors, the circumstances of which were extremely interesting. The Spaniards had left several of their flags in this village, one of which was unfurled at the Chief’s door the day of the grand council; and that among various demands and charges I gave them was that the said flag should be delivered to me, and one of the United States’ flags be received and hoisted in its place. This probably was carrying the pride of nations a little too far, as there had so lately been a great impression on the minds of young men, as to their power, consequence, etc., which my appearance with 20 infantry was by no means calculated to remove.

“After the chiefs had replied to various parts of my discourse but were silent as to the flag, I again reiterated the demand for the flag, adding “that it was impossible for the nation to have two fathers; that they must either be the children of the Spaniards, or acknowledge their American father”. After a silence of some time an old man rose, went to the door, took down the Spanish flag, brought it and laid it at my feet; he then received the American flag, and elevated it on the staff which had lately borne the standard of his Catholic Majesty. This gave great satisfaction to the Osage and Kans, both of whom decidedly avow themselves to be under American protection. Perceiving that every face in the council was clouded with sorrow, as if some great national calamity were about to befall them, I took up the contested colors and told them “that as they had shown themselves dutiful children in acknowledging their great American father, I did not wish to embarrass them with the Spaniards, for it was the wish of Americans that their red brethren should remain peaceably around their own fires, and not embroil themselves in any disputes between the white people; and that for fear the Spaniards might return there in force again, I returned them their flag, but with the injunction that it should never be hoisted again during our stay.” At this there was a general shout of applause, and the charge was particularly attended to.”

Pike’s original notes on his visit which included the location of the village were seized several months after his visit by the Spanish and thus the location of Pike’s Pawnee village was lost to time. In 1875 George and Elizabeth Johnson found the remains of a Pawnee village near the town of Republic, KS. The village was identified by the distinct, circular impressions that were left by the buildings as they degraded over the years. Elizabeth had been interest in the story of Pike and the Pawnee since her father had told her of it in 1874. She wondered if the village that she and her husband had discovered was the one that Pike had visited in 1806. She had read Pike’s journals and was convinced that she had found the site. However, she was aware that a similar site was located across the border in Nebraska, so she sent her husband and another man to Red Cloud, NE to investigate the site there. The two men found very little evidence of the existence of a Pawnee village in Red Cloud and returned home with the conclusion that Pike’s Pawnee village was in Kansas. Elizabeth and George would eventually purchase the land and donated 11 acres to the state of Kansas in 1901. With the donation of the land, the Kansas Legislature appropriated $3,000 to fence and mark the site. With this action, a Kansas legend was born and for the next two decades this site was believed to be a historic landmark.

On July 4, 1901, the cornerstone of the 26-foot-tall granite monument was laid in a ceremony. The dedication was held on September 30, 1901, just one day after the 95th anniversary of Pike’s visit. The President of the Pawnee Republic Historical Society spoke at the dedication and had this to say:

“We meet at this historic spot, this hall of fame, to place a tablet to the memory of one of our early heroes, and dedicate these grounds to the cause of freedom, to which he gave his young life; to perpetuate the record of one of the greatest peaceful victories of our history, a victory only possible by the rare judgement, tact, and personality of the gallant young officer Zebulon M. Pike. History places him on these grounds, over which floated the flag of one of the greatest nations of the world, surrounded by hundreds of warriors who recognized the sovereignty of that flag, while he, with a little band of travel- stained and weary men, demanded the lowering of the flag of Spain and substituting the stars and stripes. Incredible as it may seem, this demand was complied with, and on September 29, 1806, Kansas breezes were called upon for the last time to unfurl that flag which has floated over more of misery, more of oppression, more of treachery, than any emblem ever designed by man.”

Five years later in Sept. 1906 there was a four-day celebration held at the site to honor the 100th anniversary of the 1806 visit.

The popularity of what has become known as the Pike-Pawnee flag Incident grew as a Kansas Historical event after the erection of the Monument. It was noted in the 1926 book, History of Kansas: State and People: “The incident of the flag came to be a matter of pride to the Kansas people. There is nothing like it in the history of any other state.”

There is no evidence that this event, if it did indeed happen in Kansas, was the first flag raising in the state. It is more probable that the first flag raising was by Lewis and Clark when they passed through the Northeast corner of present-day Kansas in 1804. The story of the Pike/Pawnee flag incident continued to reappear in books that were published later than 1953 and was the topic of a speech given at the rededication of the monument in 1996 by the Historian General of the National Society of the Daughters of the American Revolution.

What is interesting is that this Kansas legend continues to endure long after the Kansas Historical Society and other experts in the field of Kansas History conceded that the actual event happened in Nebraska. Though the Kansas site was accepted by the state of Kansas as Pike’s Pawnee village and was marked as a historic site. However, due to indications of the distances traveled by Pike and his company as well as landmarks described by him in his journal is was believed that Pike’s real village was located to the North and West of the Kansas site. It was not until 1923 that a village fitting the description that Pike gave was identified in Nebraska by A.T. Hill who, while in Kansas, had attended the dedication at the Kansas site. He became so intrigued by the story that he began to read journals that described the event and concluded that the state had made a mistake and marked the wrong site. He moved to Nebraska and began to search for the real site. Through interviews, he found his way to a farm owned by George Dewitt who recalled that before his father who homesteaded the area in 1872 that the land had been covered with lodge circles and other evidence of an Indian village. Hill went to the site and excavated, finding evidence of white contact, a Spanish bridle bit and spur. He then notified the Superintendent of the Nebraska State Historical Society. In 1925 he purchased the land to continue to investigate and preserve what remained of the village. That same year the Nebraska History Magazine presented both sides of the Kansas- Nebraska debate and eventually the Kansas State Historical Society would acknowledge Nebraska’s claim to the location of Pikes Pawnee village. Though it wouldn’t be until the early 1990s that the exhibits and the Pawnee Indian Museum were redesigned to indicate a more historically accurate view of the Kansas Monument site and its importance.

Because of its almost sacred stature as Pike’s Pawnee village the site in Kansas was preserved and has given both historians and archaeologists alike valuable information on the early history of the state. The part of the site that was saved includes 22 earth lodge depressions, a number of storage pit depressions, and the remains of the fortification wall. Two of the house depression were excavated in 1949 but intensive excavation of the site did not occur until 1965 under the direction of the Kansas State Archeologist Tom Witty. The museum was constructed around one of the largest of the lodge depressions before it was excavated in 1967. Only eight of the 22 lodge depressions have ever been excavated. The site was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1971. Today it is operated by the Kansas Historical Society as the Pawnee Indian Museum State Historic Site. There is a state historical marker placed near the monument that explains the mistake made by the state about the location of Pike’s village. Nebraska may be able to claim the Pawnee Indian village that Pike visited but due to farming, which destroyed much of the evidence of its existence, the site in Kansas is the only preserved Pawnee village in the central plains. The story of Pike and the Pawnee is still a noteworthy Kansas legend and one that will persist for years to come.

Thanks for reading. Be sure to share and subscribe. You can also help support independent journalism in Kansas by buying me a coffee at buymeacoffee.com/kscon.

Emily Brannan

Emily Brannan is a born and raised Kansan. Graduating from Missouri Southern State University in Joplin, MO with a Bachelor of Arts in History with a minor in American Studies, she is now a historian, writer, and researcher.